Battle of Karnal

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2024) |

| Battle of Karnal (1739) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Nader Shah's invasion of India | |||||||||

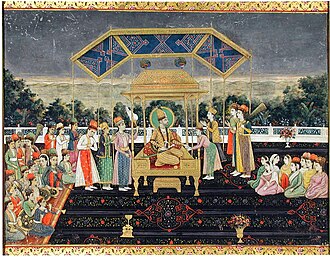

Painting of the Battle of Karnal from the palace of Chehel Sotoun | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Persian officers |

Mughal officers

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

55,000 with a war-camp of 160,000 (mounted and armed)[6][7][8][9]

|

75,000[6][10][11][12] to 300,000 (including non-combatants)[9][13][14][15]

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 1,100 to 2,500 with 5,000 wounded[10][16][17] | 8,000–10,000[10][16] to 20,000–30,000[13] | ||||||||

The Battle of Karnal (Persian: نبرد کرنال) (24 February 1739)[18] was a decisive victory for Nader Shah, the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran, during his invasion of India. Nader's forces defeated the army of Muhammad Shah within three hours,[19] paving the way for the Iranian sack of Delhi. The engagement is considered the crowning jewel in Nader's military career as well as a tactical masterpiece.[13][20][21] The battle took place near Karnal in Haryana, 110 kilometres (68 mi) north of Delhi, India.[1] As a result of the overwhelming defeat of the Mughal Empire at Karnal, the already-declining Mughal dynasty was critically weakened to such an extent as to hasten its demise. According to Axworthy, it is also possible that without the ruinous effects of Nader's invasion of India, European colonial takeover of the Indian subcontinent would have come in a different form or perhaps not at all.[13]

Nader's entry into the Mughal Empire

[edit]The events at the Delhi court during Nadir’s invasion reveal a story of shocking inefficiency. News of Kabul’s loss in June 1738 reached Delhi in early July, yet nothing was done to secure the borders for many months. Even after Nadir Shah crossed the Khayber Pass in November, it was two months before any decisive action was taken. On 2 December 1738, the Emperor officially permitted his three top nobles—Itimad-ad-Daula, Qamar-ud-Din Khan (the wazir), Nizam-ul-Mulk, Asaf Jah I (the regent), and Samsam‑ud‑daulah Khan Dauran (the military head)—to move against the invader and provided them with funds. Instead of promptly addressing the threat, however, they set up camp outside Delhi in the Shalimar Garden near Sarai Baoli and wasted an entire month.[22]

When news came on 10 January 1739 that Nadir Shah had crossed the river at Attock, the imperial army was finally urged to act. The court still placed its hopes on Governor Zakariya Khan to make a stand, but when he proved unable to resist Nadir Shah, some courtiers even accused him of treachery—alleging that he had surrendered Lahore fort to the Persians because of his shared background with Nadir.[22][6][23] .[22]

At the first sign of Nadir Shah’s advance, the court recognised its own shortcomings and called on the experienced Nizam for advice. A veteran of Aurangzeb’s era, the Nizam was known for his wisdom and diplomacy, yet he was not given full command or the confidence of the Emperor, whose trust lay with Khan Dauran and the local faction. Khan Dauran, who admired Rajput bravery, even sent messengers to call on his protégés among the Hindu Rajputs, especially Sawai Jai Singh, to aid the Emperor. However, longstanding alienation had left the Rajput chieftains reluctant to act, with many now seeking independence and even inviting the Marathas to help dismantle the Empire. The Emperor eventually appealed to Baji Rao for help, and the Peshwa promised to send the Malwa force under leaders such as Malhar Rao Holkar, Ranuji Sindhia, and Udaji Puar. Nevertheless, this expected assistance never arrived in time. Not only did no Dakhini force come to aid at Karnal, but the Maratha envoy even fled, and Baji Rao later considered defending the Narmada line to block further advances by Nadir. A coordinated Maratha defence of northern India simply did not happen.[22]

The imperial forces spent the month of Ramzan (December 1738) outside Delhi without any significant action. Once it was confirmed that the Persians had crossed at Attock, the three nobles finally began marching toward Lahore on 10 January 1739, urging the Emperor to join them immediately. Soon after, they reached Panipat, where on that same day Muhammad Shah left Delhi and later joined his generals who had been waiting. By that time, news of Nadir’s capture of Lahore had already reached the court, making it impossible to save the city. It was then decided to set up camp and await the enemy at Karnal, a location with abundant water from a canal and open plains suitable for manoeuvring large cavalry units. This pause also allowed time for additional forces, including 30,000 horsemen from the governor of Oudh and reinforcements from Rajputana, to join. Advised by the Nizam, the Emperor’s counsellors decided to fortify their position at Karnal rather than risk an immediate battle. Under the direction of Sad‑ud‑din Khan Mir Atash, the camp was enclosed by a long mud wall with artillery arranged along it, and soldiers were stationed in trenches to keep constant watch.[24][22]

Muhammad Shah gathers a large force

[edit]Rustam Ali estimates that the Persian force at Karnal numbered about 55,000 mounted soldiers—a figure believed to be nearly accurate. According to Mirza Mahdi’s account, Nadir Shah had left Persia with around 80,000 men. Even though he recruited Afghans along the way and possibly got extra troops from his homeland, he had to set aside many soldiers to hold conquered forts, secure his long communication line, and escort his eldest son back to Persia. Hanway notes that when Nadir reached Tilawri (near Azimabad), he had 40,000 men with him, not counting those in his front and rear. In total, his camp contained roughly 160,000 people. About one-third of these were servants who were mounted—and some were fully armed—so they could help in raiding or protecting the baggage. There were also over 6,000 women, dressed in large crimson coats much like the men’s, making them hard to distinguish from afar.[25][22]

Conquests by Nader's invading army had caused much consternation at the Mughal court of Muhammad Shah residing in Delhi. Nizam‑ul‑Mulk was summoned to the Emperor's presence, and many summons were sent out across northern India for the contribution of military forces. 13 December saw the Mughal army march out of Delhi to confront the invading forces to the north. The enormity of its size was such that the length of the column was 25 kilometres and the width was 3 kilometres. Muhammad Shah himself joined this army. Due to the cumbersome size of the Mughal army, Muhammad Shah could not take his forces any further than Karnal, approximately 120 kilometres north of Delhi. In total, Muhammad Shah commanded a war‑camp of 300,000 troops—including non‑combatants—equipped with 3,000 guns along with 2,000 war elephants. Out of these, the forces deployed on the field numbered 75,000.[6][26] Despite the large numbers at the Mughal's disposal, they suffered from obsolescent war material and antiquated tactical systems. Almost all of the guns in the army were far too large in calibre to be considered field artillery, as they were practically impossible to manoeuvre during battle and took such a long time to reload that they would have minimal effect even in cases of correct utilisation. In contrast, most of Nader's artillery was lighter and much more manoeuvrable than that of their Mughal counterparts, as well as the zamburaks, which provided extra mobile fire power. In contrast to the Mughal army's infantry, all of the 20,000 Persian musketeers (jazyarechi) were uniformed, drilled, and homogeneously organised. Although the 50,000 cavalry contingent in the Mughal army was of excellent quality, there was nothing to suggest a common and cohesive underlying military structure set out for their deployment and use. The Persian cavalry was composed of two parts: the state troops, which were trained and drilled via a uniform system, and the auxiliary troops, which were recruited into the Imperial army after the conquest of their homeland.[27]

Preparetion

[edit]Karnal is located on an ancient highway between Delhi and Lahore, positioned north of the Mughal capital and Panipat and just south of Taraori, a place known for many historic battles. Even Kurukshetra, famous for the legendary war between the Pandavas and Kauravas, is nearby. This setting made Karnal a natural stage for a major battle between Indian and Persian forces.[22][28][29][30]

The town is bordered on the east by a canal built by Ali Mardan Khan. Between this canal and the Jamuna River lies a broad, flat plain suitable for large-scale cavalry maneuvers. Muhammad Shah had set up a fortified camp along the west bank of the canal, with Karnal lying immediately to its south. To the north, the land changes from a dense jungle to an open plain, offering natural protection: the jungle guarded the front while the canal defended the right side. The Mughal army was arranged with the Nizam in the lead, supported by artillery, the Wazir on the left, the Emperor in the center, and Khan Dauran on the right.[22][29][30]

In February 1739, Nadir Shah reached Sarai Azimabad early one morning. Elite horsemen from Kurdistan, led by Haji Khan, had already scouted along both sides of the canal and gathered intelligence at the edge of the Mughal camp. With this information, Nadir Shah decided against a frontal attack. Instead, he moved east of Karnl, staying near the Jamuna for water, and planned to cut off the Mughal communication line with Delhi by taking Panipat from behind. His goal was to force Muhammad Shah either to leave his strong position and fight on Persian terms or to remain trapped while the Persians advanced toward Delhi.[22][29][30]

Before dawn the next day, the Persian army left Sarai Azimabad, crossed the canal well to the east of the town, and set up camp on a flat plain northeast of Karnal, near Kunjpura and in sight of the Jamuna. At the same time, Nadir Shah rode close to the Mughal camp to assess its strength and layout before returning to his tents. Later that evening, he learned that Saadat Khan was arriving at Panipat with a large force of cavalry, artillery, and supplies to aid the Mughal Emperor. In response, the Persians sent one division to intercept him and another strong unit to threaten the camp’s eastern flank, while smaller groups of skirmishers moved in to cut off any potential reinforcements.[22][29][30]

Battle

[edit]

On the fateful Tuesday morning of February 13, 1739, the Persian army moved out in three separate groups along a wide plain between a canal and the Jamuna river. The center force, led by Prince Nasr-ullah, was ordered to leave the riverbank and take up a position directly north of the Mughal camp where it could face the division commanded by the Nizam. Meanwhile, Nadir Shah, heading the lead group, first reached a point opposite the Mughal position along the canal. However, when he learned that Saadat Khan had joined the Mughal Emperor during the night, he quickly veered to his left and set up his camp on a large, open field a short distance east of the enemy and close to the river. His son soon arrived to join him at this new central position. By mid-morning, as the sun began to lower from its highest point, the Mughal soldiers unexpectedly emerged from their lines, ready to fight.[22][29][30]

Inside the Mughal camp, the situation was already tense. Responding to the Emperor’s urgent call for help, Saadat Khan had left his home province of Oudh with 20,000 cavalry, along with artillery and war supplies. He had marched continuously for a month, stopping briefly only in Delhi on February 7 before quickly moving on. Covering a long distance in just a few days, he pushed on through Panipat and, on February 12, made a final determined effort to cover the last stretch, arriving at Karnal by midnight with the main force. Unfortunately, his baggage train lagged far behind in an unprotected line—a common issue with Indian armies.[22][29][30]

Meanwhile, Persian scouts had advanced from their camp and gathered clear information about Saadat Khan’s position. The Mughal intelligence, however, had failed to notice these movements and had not taken steps to safeguard their baggage. According to an account by Ghulam Husain, no one in the camp was aware of Nadir Shah’s imminent arrival from Lahore until some local fodder collectors, who had gone out to fetch food, returned injured and terrified after a sudden encounter with Persian scouts, crying out that “Nadir has come!” This news spread quickly, causing panic in the camp and increasing the urgency for reinforcements.[22][29][30]

Shortly after midnight on February 12, Saadat Khan arrived near Karnal. Khan Dauran met him well before he reached the main camp and escorted him in. The next morning, after the usual greetings with the Emperor, a war council was held to discuss battle plans. During these discussions, word arrived that small groups of Persian skirmishers had attacked Saadat Khan’s baggage train and stolen 500 loaded camels. Reacting quickly, Saadat Khan grabbed his sword—previously set aside before the Emperor—and asked for permission to immediately leave and engage the enemy. However, the Nizam advised waiting, arguing that the Oudh soldiers were exhausted from a month of constant marching and needed a rest to be battle-ready. He also pointed out that there were only a few hours of daylight left for fighting, and that the troops had not been alerted early enough to form proper battle lines. Khan Dauran added that without sufficient time to assemble and arm themselves, the soldiers would be at a disadvantage. Some courtiers even remarked that the loss of 500 camels was trivial compared to what Saadat Khan could achieve; if he managed to defeat Nadir Shah in a well-prepared battle the next day, they believed the entire Persian camp and its treasures would soon be captured.[22][29][30]

However, he refused to take the advice and insisted on rescuing his camp followers. He sent out heralds to announce that all his soldiers should gather and follow him, and he quickly moved toward the attack point with only his escort and the immediately available troops—about a thousand cavalry and a few hundred infantry—but without any artillery. Since each Indian cavalryman relied on his own horse, he was very cautious about risking or tiring it, especially after a month of continuous riding. As a result, many soldiers initially declined to move, arguing that since their leader had gone to see the Emperor, he could not have ordered them to fight. Nevertheless, around 4,000 cavalry and 1,000 infantry eventually joined him.[22][29][30]

When Saadat Khan reached the field, the Persian light troops pretended to retreat. He chased after them, which drew him approximately two miles away from his own camp. Realizing the tactical situation, he immediately sent messengers to the Emperor asking for reinforcements to secure victory. Muhammad Shah then consulted the Nizam, who pointed out that since the battle was occurring on the eastern side of the camp, Khan Dauran—commanding the division closest to that area (the Right Wing)—should move forward. Khan Dauran promptly set out on an elephant without waiting to gather his entire force or arrange his artillery. His popularity was such that many soldiers, upon hearing he had taken the initiative, joined him in successive groups until he had around 8,000 horsemen with him.[22][29][30]

Later in the afternoon, the Emperor himself emerged from his tents with the Wazir and positioned himself with organized troops by the canal, but he appeared more as an observer than an active combatant. Due to delays in the start of the various divisions, the lack of a common battle plan, and the absence of a single leader directing operations, the three divisions ended up separated by more than a mile from one another. In this formation, Saadat Khan led the Right Wing near the Jamuna, Khan Dauran’s division formed the Center in the middle of the plain, and the Wazir along with the Emperor constituted the Left Wing by the canal. Gradually, as more imperial troops arrived, they assembled into a large mass stretching from their camp to the battlefield, with noticeable gaps between the groups. The Left Wing, under the Emperor, had even drawn out their field artillery from behind the trenches and set up small tents for their officers, yet they did not engage the enemy.[22][29][30]

In summary, the Indian army resembled a disorganized mob without true unity or a clear command. Most of its forces remained inactive and distant from the fight, contributing little to the struggle; their overwhelming numbers only resulted in greater chaos during the retreat. Meanwhile, the agile Persian forces, led by the finest general in Asia, skillfully engaged or avoided the enemy as the situation demanded, and Nadir Shah’s strategic brilliance ultimately countered the Indians’ numerical advantage and the determined courage of many of their soldiers.[22][29][30]

A little after midday on February 13, 1739, news reached Nadir Shah that Saadat Khan’s army was coming out onto the plain. This pleased him greatly, for as his court historian noted, he had long awaited such an opportunity—a chance for a battle of maneuvers where his military skill could shine since the Indian army had been drawn out from its strong defensive position.[22][29][30]

Nadir Shah quickly put his plans into action so that his forces would finish their work before nightfall. He left one division behind to protect his camp, placed the center under the command of his son Nasr-ullah—who had many renowned warriors and a powerful artillery—and took charge of the vanguard himself. He arranged 3,000 of his finest soldiers into three separate bodies and hid them in ambush. In addition, he sent two smaller groups of 500 fast horsemen each toward Saadat Khan and Khan Dauran to lure them further into the field. Clad in full armor and wearing a decorated helmet, Nadir Shah then mounted a swift horse and led 1,000 carefully chosen Turkish horsemen from his own Afshar clan into battle to direct the fighting.[22][29][30]

The entire Persian army was made up of cavalry. Their artillery included long muskets or swivel-guns known as jazair—about seven or eight feet long, each fitted with a support prong—as well as long swivel pieces called zamburaas that fired one- or two-pound balls. Each of these heavy pieces was mounted on a camel trained to lie down on command, so that when the guns were fired, the camel’s back could provide a stable firing platform. To counter the Indian elephants, which played an important role for them, Nadir Shah had special platforms built across two camels. These platforms were loaded with naphtha and other flammable materials, with orders to set them alight during the fight; the sight of approaching fire would scare the elephants, throwing the Indian army into disarray.[22][29][30]

Meanwhile, Persian skirmishers successfully covered their main position where Nadir Shah had arranged his 3,000 best troops. He had dismounted his swivel-guns and lined them up along the front, with their barrels resting on supports.[9][22] At just after one o’clock in the afternoon, the battle began with both sides releasing a volley of arrows. The Persian scouts pretended to retreat by turning back in their saddles while firing their bows and muskets—an echo of tactics used by their Parthian ancestors. Saadat Khan gave chase, which led him into an ambush located three or four miles east of the imperial camp and away from the protection of its artillery. Suddenly, the Persian cavalry screen moved aside, and hundreds of swivel-guns opened fire at point-blank range. The foremost and bravest of Saadat Khan’s troopers were killed, and after enduring this fierce barrage for only a short time, his vanguard broke and fled. Despite this, Saadat Khan held his ground with a loyal band of followers who fought until they were all killed. However, by early evening, he was forced to leave the field, and fighting on the extreme right of the Mughal army ended.[22][29][30]

A similar fate met Khan Dauran’s division in the center, though he managed to hold out a bit longer. The rapid-fire discharge from the Persian swivel-guns decimated his forces before they could even respond. Nadir Shah’s brilliant tactics, combined with the lack of effective leadership and poor planning among the Indian commanders, had split the three divisions of the imperial army by over a mile. This separation meant that each division could only hear the distant sound of fighting from the others and had no idea of the struggles facing their comrades. As a result, even though Khan Dauran wished to assist Saadat Khan, he could not coordinate his efforts. The Nizam, considered the most capable Mughal general, remained completely inactive throughout the day and offered no help—possibly because, as some suggest, he hoped to take over if his rivals perished. The Emperor, meanwhile, appeared almost lifeless on the extreme left. At the points where the armies met, the Mughal's were outnumbered and too far from their heavy artillery. Their commanders, riding on tall elephants, became easy targets for the enemy’s fire, while the quick Persian horsemen remained safely out of reach.[22][29][30]

For two hours, Nadir Shah’s gunners unleashed deadly fire. Although the Indians fought bravely, they lost many lives in a futile effort—“arrows cannot answer bullets,” as one contemporary put it. When the battle became utterly hopeless and most of their officers were killed, about 1,000 of Khan Dauran’s bravest soldiers dismounted and, following the Indian custom of tying the skirts of their long coats together, fought on foot until they all fell. Khan Dauran himself was mortally wounded in the face and fell unconscious on his backside. Yet a small group of his loyal retainers, led by his steward Majlis Rai, managed to surround his elephant and, through desperate fighting, bring him back to camp near sunset—though he died not long after.[31][32][33][9]

For three months, Saadat Khan suffered from a leg injury that made it impossible for him to walk or ride, so he was always conveyed in a chair or on an elephant. Even though he had already received two wounds in battle, he might have been able to withdraw safely if not for an unforeseen mishap. His situation worsened when the enraged elephant of his nephew, Nisar Muhammad Khan Sher Jang, charged his own elephant, forcing it into the Persian ranks despite his men’s desperate attempts to slow it down by stabbing it with swords and daggers. Surrounded by foes, Saadat Khan kept shooting arrows in a bid to avoid capture. At that moment, a courageous young Persian soldier from his native Naishabur rode up on an elephant, addressing him by the familiar name “Muhammad Amin” and shouting, “Are you mad? Whom are you fighting, and on whom do you continue to rely?” The soldier then fixed his spear into the ground, looped the reins of his horse around it, and climbed up to Saadat Khan’s howda using the rope hanging down from it. Consequently, the Khan surrendered and was taken to Nadir’s camp.[22][29][30]

With these two leaders removed from the field, the Indian army broke apart, while Persian horsemen pursued them with heavy slaughter. The Emperor and his nobles had taken up a battle line beside a canal at the extreme west of the field, bracing themselves for an attack. However, Nadir Shah held his forces in reserve rather than assaulting the well-fortified position with its heavy artillery, since he had a more certain and easier method to force the Emperor’s submission. At sunset, Muhammad Shah retired to his camp, having done nothing to save his throne or protect his people. The battle, which began at the time of the zuhar prayer and ended at the osar prayer, lasted for less than three hours.[35][36][37] [38][39][40][21] [41]

Losses and consequences

[edit]

The Mughals suffered far heavier casualties than the Persians. Exact figures are uncertain as accounts of that period were prone to bombast. Various contemporary commentators estimated Mughal casualties being up to 30,000 men slain with most agreeing on a figure of around 20,000 and with Axworthy giving an estimate of roughly 10,000 Mughal soldiers killed. Nader himself claimed that his army slew 20,000 and imprisoned "many more".[42] The number of Mughal officers slain amounted to a staggering 400.[43] Though as a proportion of the entire Mughal army the actual casualties suffered were not excessive, this masks the fact that the casualties constituted the very best of the Mughal army, including an overwhelming number of its leaders.

The Mughals had been defeated in part due to their outdated cannons. In addition, Indian elephants were an easy target for Persian artillery and Persian troops were more skilled with a musket.[44]

Recent scholarship gives an estimate of the total Persian casualties at a mere 1,100 including 400 killed and 700 wounded.[17] This number comprised such a small fraction of the Persian army as to be negligible.

Although the meeting was initially tense, with the Mughal plenipotentiaries arriving with armour instead of plain clothing, Nader soon requested that he and Nizam-ul-Mulk be left alone to discuss matters more freely. Once alone with the Shah, Nizam-ul-Mulk humbly claimed that his life was entirely at his mercy. Nader impressed upon him the importance of Muhammad Shah agreeing to pay an indemnity to the Persian crown. Having convinced Nizam-ul-Mulk to request the Mughal Emperor's personal presence in the Persian camp, Nader sent him away.

26 February saw the Mughal Emperor travel to meet with his Persian counterpart amongst much pomp and circumstance. Nader paid Muhammad Shah the respect worthy of an Emperor and conversed with him in Turkic. After making obeisance, Nader Shah remarked, "Brother, you have three faithful servants, and the rest are traitors; those three are Nasir Khan, Khan-i Dauran Khan and Muhammad Khan; from these I have received no letters."[45] After the conclusion of the negotiations the Mughal party returned to their encampment west of Alimardan river.

Mughal submission and sacking of Delhi

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

.

Mughal Uprising and sack of Delhi

[edit]

Rumours began spreading amongst the populace of Delhi that a gratuitous levy was imminent. There were also tales of Muhammad Shah seizing Nader and or having him killed one way or another. When a rumour broke out that Nader himself had been assassinated, a posse of Delhi citizens gathered around a granary as a group of Persian soldiers had been sent to negotiate prices, and the posse attacked and killed five Persian soldiers. The event sparked an uprising, and bands of civilians swept through the city and targeted isolated Persian soldiers in succession. When news was taken to Nader, he was dismissive, believing his soldiers were seeking out a pretext to ransack the city. But after successive reports of lynchings, Nader sent one of his retainers to verify these claims. He sent another of his inner circle also, but both were killed by the baying crowds. Nader sent out a fowj (a thousand-strong unit) but ordered them to engage only those involved in the violence.[46][47]

Three thousand soldiers marched out of the mosque's courtyard and began a gruesome and blood-curdling mass killing. Nader Shah "sat with sword in hand, wearing a solemn face steeped in melancholy and lost in deep thought. No man dared break the silence."[48] Smoke rose above the city with ceaseless sounds of suffering and pleading echoing throughout. There was sparse resistance and most people were killed with no fighting chance. Many men were arrested and taken to the river Yamuna where they were all beheaded in cold blood. The soldiers entered houses and killed all the inhabitants, plundered all the riches they found and then set fire to what remained. The murder and rapine was such that many men chose to kill both themselves and their families instead of being subjected and slaughtered by the Persian soldiery.

Nader sent forth 1,000 cavalrymen to each district of the city to ensure the collection of taxes. But perhaps the greatest riches were plundered from the treasuries of the Mughal dynasty's capital. The Peacock Throne was also taken away by the Persian army, and thereafter served as a symbol of Persian imperial might. Among a trove of other fabulous jewels, Nader also gained the Koh-i-Noor ("Mountain of Light") and Darya-ye Noor ("Sea of Light") diamonds. It is estimated that the total worth of the treasures plundered came to perhaps 700 million rupees. This was roughly the equivalent to £90 million sterling at the time, or £8.2 billion sterling in the early 21st century.[49]

Persian troops left Delhi at the beginning of May 1739, also taking with them thousands of elephants, horses, and camels, all loaded with the booty they had collected. The plunder seized from India was so rich that Nader stopped taxation in Persia for a period of three years following his return.[50] On Nader's return to Iran, Sikhs fell upon Nader's army and seized a large amount of booty and freed the slaves in captivity.[51][52][53][54] The Maathir-ul-Umara states that Khudayar Khan answered:[55]

"We from the time of our forefathers were the servants of the King of India, if we had shown an inclination for you, you would not have believed us."

Historic ramifications

[edit]Nader Shah's victory against the crumbling Mughal Empire in the East meant that he could afford to turn to the West and face Persia's archrivals, the Ottomans, once again. The Ottoman Sultan Mahmud I initiated the Ottoman–Persian War (1743–1746) in which Muhammad Shah closely co-operated with the Ottomans, as well as after, until his death in 1748.[56] Nader's Indian campaign alerted the British East India Company to the extreme weakness of the Mughal Empire and the possibility of expanding British imperialism to fill the power vacuum.[57]

As a result of the defeat of the Mughal Empire at Karnal, the already-declining Mughal dynasty was critically weakened to such an extent as to hasten its demise. According to Axworthy, it is also possible that without the ruinous effects of Nader's invasion of India, the European colonial takeover of the Indian subcontinent would have come in a different form or perhaps not at all, which would have fundamentally changed the history of the Indian Subcontinent.[57]

See also

[edit]- Military of the Afsharid dynasty of Persia

- Mughal dynasty

- Afsharid dynasty

- Battle of Khyber Pass

- Iranian Crown Jewels

- Nadir Shah's invasion of India

References

[edit]- ^ a b Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History, 4th Ed., (HarperCollinsPublishers, 1993), 711.

- ^ David Marshall Lang. Russia and the Armenians of Transcaucasia, 1797–1889: a documentary record Columbia University Press, 1957 (digitalised March 2009, originally from the University of Michigan) p. 142.

- ^ Valeri Silogava, Kakha Shengelia. "History of Georgia: From the Ancient Times Through the "Rose Revolution" Caucasus University Publishing House, 2007 ISBN 978-9994086160 pp. 158, 278.

- ^ Zahiruddin Malik (1973). A Mughal Statesman Of The Eighteenth Century. p. 101.

- ^ Yadava, S. D. S. (2006). Followers of Krishna: Yadavas of India. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7062-216-1.

- ^ a b c d Sarkar, J., Nadir Shah in India, p. 38 [1].

- ^ Floor, Wiilem(2009). The rise & fall of Nader Shah: Dutch East India Company Reports 1730–1747, Mage Publishers.

- ^ Floor, Willem(1998). new facts on Nadir Shah's campaign in India in Iranian studies, pp. 198–219.

- ^ a b c d Jaques, Tony (2006), "Karnal-1739-Nader Shah#Invasion of India", Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity through the Twenty-first Century, Westport, CT: Greenwood, p. 512

- ^ a b c Kaushik Roy, War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849, p. 32 "75,000"&pg=PA32.

- ^ A Comprehensive History of India: 1712–1772, p. 69 "75,000".

- ^ Sinha N.K, Bannerjee A.C., History of India, p. 458 "75,000".

- ^ a b c d Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant, p. 254. I. B. Tauris.

- ^ Mohammad Kazem Marvi Yazdi, Rare views of the world" 3 vols., Ed Amin Riahi, Tehran, Third Edition, 1374.

- ^ "History of Nadir Shah's Wars" (Taarikhe Jahangoshaaye Naaderi), 1759, Mirza Mehdi Khan Esterabadi, (Court Historian).

- ^ a b Sarkar, J., Nadir Shah in India, p. 51 [2].

- ^ a b Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant, p. 263. I. B. Tauris.

- ^ "India vii. Relations: The Afsharid and Zand – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ Sarkar, Jagadish Narayan. A Study of Eighteenth Century India: Political history, 1707–1761 Saraswat Library, 1976. (Volume 1 of A) original from the University of Virginia. p. 115.

- ^ Quoted in Christopher Bellamy, The Evolution of Modern Land Warfare: Theory and Practice (London, 1990), 214.

- ^ a b Moghtader, Gholam-Hussein(2008). The Great Batlles of Nader Shah. Donyaye Ketab.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Sarkar, Sir Jadunath (1973). Nadir Shah in India. Naya Prokash. pp. 26–65.

- ^ Dalrymple, William; Anand, Anita (2017). Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 52–60. ISBN 978-1408888827.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant, p. 255. I.B. Tauris.

- ^ Ghafouri, Ali (2008). History of Iran's wars: from the Medes to now, p. 383. Etela'at Publishing. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Kaushik Roy, War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849, p. 32 "75,000"&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjWmIXSu-LoAhVI73MBHa7dB_sQuwUIMTAB#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Ghafouri, Ali (2008). History of Iran's wars: from the Medes to now, p. 383. Etela'at Publishing. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Mehta, Jaswant Lal (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707-1813. pp. 149–152. ISBN 9781932705546.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Irvine, William (1922). Later Mughals. Vol. 2. Calcutta: M. C. Sarkar & Sons. pp. 330–360.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Sharma, S. R. (1999). Mughal Empire in India: A Systematic Study Including Source Material. Vol. 1. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 727–740. ISBN 9788171568178.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael, The Sword of Persia; Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant, I B Tauris, 2009. p. 257.

- ^ G. S. Cheema (2002). The Forgotten Mughals: A History of the Later Emperors of the House of Babar, 1707–1857. Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 195. ISBN 9788173044168.

- ^ Moghtader, Gholam-Hussein (2008). The Great Battles of Nader Shah. Donyaye Ketab.

- ^ Hanway, Jonas, An Historical Account of the British Trade, 1: 251–253.

- ^ Satish Chandra (1959). Parties And Politics At The Mughal Court. Oxford University Press. p. 245.

- ^ Sir Jadunath Sarkar (1920). The Mughal Administration. Superintendent, Government Printing, Bihar and Orissa. p. 17.

musketeers were mostly recruited from certain Hindu tribes , such as the Bundelas , the Karnatakis , and the men of Buxar

- ^ Ghosh, D. K. Ed. (1978). A Comprehensive History Of India Vol. 9. Orient Longmans.

The Indian muslims looked down upon fighting with muskets and prided on sword play. The best gunners in the mughal army were hindus

- ^ William Irvine (2007). Later Muguhals. Sang-e-Meel Publications. p. 668.

- ^ J.J.L. Gommans (2022). Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire 1500–1700. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134552764.

- ^ "History of Nadir Shah's Wars" (Taarikhe Jahangoshaaye Naaderi), 1759, Mirza Mehdi Khan Esterabadi, (Court Historian).

- ^ Michael Axworthy (2010). Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 202. ISBN 9780857724168.

- ^ Brigadier-General Sykes, Sir Percy (1930). "A history of Persia, Vol. II", third edition, p. 260. Macmillan & Co.

- ^ "La stratégie militaire, les campagneset les batailles de Nâder Shâh – La Revue de Téhéran – Iran". teheran.ir. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ Axworthy 2009

- ^ William Irvine (1878). the Bangash Nawab of Farrukhabad. p. 332.

- ^ Axworthy p. 8.

- ^ "An Outline of the History of Persia During the Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722–1922)". Edward G. Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 33. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ Malcom, History of Persia, vol 2, p. 85.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael, Iran: Empire of the Mind, Penguin Books, 2007. p. 159. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Cust, Edward, Annals of the wars of the eighteenth century, (Gilbert & Rivington Printers: London, 1862), 228.

- ^ Hari Ram Gupta (1999). History of the Sikhs: Evolution of Sikh confederacies, 1708–69. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 54. ISBN 9788121502481.

- ^ Vidya Dhar Mahajan (2020). Modern Indian History. S. Chand Limited. p. 57. ISBN 9789352836192.

- ^ Paul Joseph (2016). The Sage Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives. Sage Publications. ISBN 9781483359908.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi (1999). Revenge and Reconciliation: Understanding South Asian History. Penguin Books. pp. 117–118. ISBN 9780140290455.

- ^ Beveridge, H., Tr. (1941). The Maathir-ul-umara Vol. 1. p. 819.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Naimur Rahman Farooqi (1989). Mughal-Ottoman relations: a study of political & diplomatic relations between Mughal India and the Ottoman Empire, 1556–1748. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b Axworthy p. xvi.

Bibliography

[edit]- Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia; Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I B Tauris.

- Cust, Edward, Annals of the wars of the eighteenth century, Gilbert & Rivington Printers: London, 1862.

- Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History, 4th Ed., HarperCollinsPublishers, 1993.

- Mohammad Kazem Marvi Yazdi, Rare views of the world 3 vols., Ed. Amin Riahi, Tehran, 3rd Ed., 1374

External links

[edit]- Nadir Shah's invasion in India (archived)

- Battle of Karnal 1739 – History of Haryana[usurped] (archived)